Ape-like feet 'found in study of museum visitors'

Scientists have discovered that about one in thirteen people have flexible ape-like feet.

A team studied the feet of 398 visitors to the Boston Museum of Science.

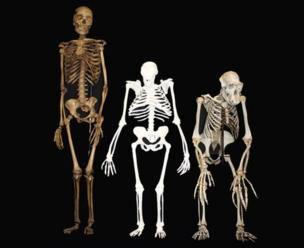

The results show differences in foot bone structure similar to those seen in fossils of a member of the human lineage from two million years ago.

It is hoped the research, published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, will establish how that creature moved.

Apes like the chimpanzee spend a lot of their time in trees, so their flexible feet are essential to grip branches and allow them to move around quickly - but how most of us ended up with more rigid feet remains unclear.

Jeremy DeSilva from Boston University and a colleague asked the museum visitors to walk barefoot and observed how they walked by using a mechanised carpet that was able to analyse several components of the foot.

Floppy foot

Most of us have very rigid feet, helpful for stability, with stiff ligaments holding the bones in the foot together.

When primates lift their heels off the ground, however, they have a floppy foot with nothing holding their bones together.

This is known as a midtarsal break and is similar to what the Boston team identified in some of their participants.

This makes the middle part of the foot bend more easily as the subject pushes off to propel themselves on to their next step.

Dr DeSilva told BBC News how we might be able to observe whether we have this flexibility: "The best way to see this is if you're walking on the beach and leaving footprints, the middle portion of your footprint would have a big ridge that might show your foot is actually folding in that area."

Another way, he added, was to set up a video camera and record yourself walking, to observe the bones responsible for this folding motion.

Most with this flexibility did not realise they had it and there was no observable difference in the speed of their stride.

In addition, Dr DeSilva found that people with a flexible fold in their feet also roll to the inside of their foot as they walk.

The bone structure of a two-million-year old fossil human relative, Australopithecus sediba, suggests it also had this mobility.

"We are using variation in humans today as a model for understanding what this human creature two million years ago was doing," added Prof De Silva.

Tracy Kivell, a palaeoanthropologist from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said: "The research has implications for how we interpret the fossil record and the evolution of these features.

"It's good to understand the normal variation among humans before we go figure out what it means in the fossil record," Dr Kivell told BBC News.

No comments:

Post a Comment